Mina Iskander was blind and had the intellect of a third-grader.

Last November, the 31-year-old man fell down an eight-foot embankment into a creek behind his Arlington adult care home. He died in December in a Fort Worth hospital.

Shannon Hunt was born with Down syndrome and developed dementia as she got older. She also needed constant supervision. Her mother and brother were shocked when they found the 48-year-old dirty and starving inside a Pflugerville group home this past August.

The caretaker was nowhere to be seen.

Iskander died a year ago. Hunt died this past fall. Their families told News 8 they are still haunted by what happened to their loved ones in those homes.

But members of the public won’t find anything on the state’s long-term care provider database about what happened to Iskander or Hunt, not by name or even by a description of the events. It’s because the information, according to the state, should not be public.

A year-long WFAA investigation has found that uncovering problems at homes like this isn’t just difficult. Texas regulators say they are prohibited by law from releasing the information because of patient privacy.

In the most recent fiscal year, more than 350 intellectually disabled people died in adult care homes in Texas, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission.

More than 60% were ruled unexpected or accidental. One was even determined to be a homicide. But no details about those deaths are public, again, because of patient privacy.

When WFAA asked for copies of the forms that adult care home operators must fill out when there’s a death of someone in their care, state regulators filed an appeal with the Texas Attorney General’s Office.

The AG’s office, which decides what information collected by the government should be released to the public, sided with regulators, saying in an opinion: “it is the specific information pertaining to individual clients, and not merely clients’ identities, that is made confidential.”

Families “would come closer to finding out about someone passing away in a group home ... by checking the media,” said Cindy Berry, co-owner of Berry Family Services, which operates hundreds of adult care homes in North Texas and advocates for best practices in the industry. “You’re going to find it there before you’ll ever find it through the state."

Texas Health and Human Services Commission officials declined to make any staff who oversee programs for the intellectually disabled available for an interview.

“Information about abuse/neglect investigations is confidential by law,” Kelli Weldon, a state HHSC spokeswoman, said in an email. “As a state agency, we must follow the laws that govern what information is protected. It would be more appropriate for you to reach out to a lawmaker or a stakeholder for comments on privacy laws since we administer these programs in accordance with state law.”

‘Safest possible environment’

Iskander and Hunt were in adult care homes for intellectually disabled people paid for by Medicaid – which is funded by taxpayer dollars.

The particular homes they were in are run by a company called EduCare Community Living, which is a corporate entity operated by ResCare, a Kentucky-based company that has similar homes across the country. ResCare recently changed its name to BrightSpring.

ResCare has faced criticism for abuse and neglect in its homes in other states, but has denied wrongdoing.

In a statement, Leigh White, an EduCare spokeswoman, said the company’s priority “is always protecting the health, well-being and safety of the individuals in our care, and we regularly evaluate and update our company protocols and policies to ensure the safest possible environment for our residents and staff.”

The company serves more than 6,000 individuals and employees about 3,500 people in Texas, the statement said.

“EduCare always takes immediate action any time a concerning incident occurs outside of normal service delivery with an individual we support,” White wrote.

‘Nothing but bones’

Shannon Hunt was healthy when she moved into a Pflugerville adult care home a year ago, her family told WFAA. Her mother and brother noticed, though, that she was losing weight and becoming more withdrawn as the months passed.

“She seemed a lot more introverted when we’d come over,” said her mother, Dorothy Fischer, who suffers from lung cancer and is on oxygen to survive. “She didn’t really even care or notice that we were there.”

For three days this past August, no one answered the phone at the home. She said something – perhaps a mother’s intuition or a higher power – told Fischer that she had to see her daughter. She and her son drove there.

They could hear Hunt hollering inside the house as they walked up to the door.

“I grabbed the door,” brother Scott Hunt said. “It was unlocked. I walked in.”

They found her on the floor in her room, clad only in a dirty diaper and a T-shirt. She was holding her stomach and yelling. She was “nothing but bones,” her mother said.

“It was very, very hard,” Fischer said.

Two other disabled women also were alone in the home. One of the women asked Scott Hunt for food. He scoured the kitchen until he found cereal and granola bars.

Paramedics took Shannon Hunt and another woman – who was legally blind and deaf -- to the hospital.

Scott Hunt said he tried, without success, to reach someone with EduCare. He said he called 911 when he couldn’t reach anyone else.

He and his mother said the caretaker returned when they’d been there for about two hours. She told them that she had been at the grocery store.

Pflugerville police continue to investigate to determine if the caregiver will face any charges. The Hunts said EduCare never offered an explanation or an apology for what happened.

The family moved Shannon Hunt into a nursing home. For a while, they said, she improved. But last month, her condition deteriorated, and she ended up in the intensive care unit.

She died Oct. 18.

Her family believes her downward spiral can be directly traced to her time in the EduCare group home.

“Though we deliver thousands of positive outcomes every day, we are deeply concerned any time an individual we support is compromised or harmed,” White, the EduCare spokeswoman, wrote in a statement to WFAA. “We strive for conscientious and compassionate care in the services provided, promoting people-first principles at all times.

“In Pflugerville, the Direct Service Provider on duty during the incident was terminated per company policy,” White added.

‘Nobody wants to say the truth’

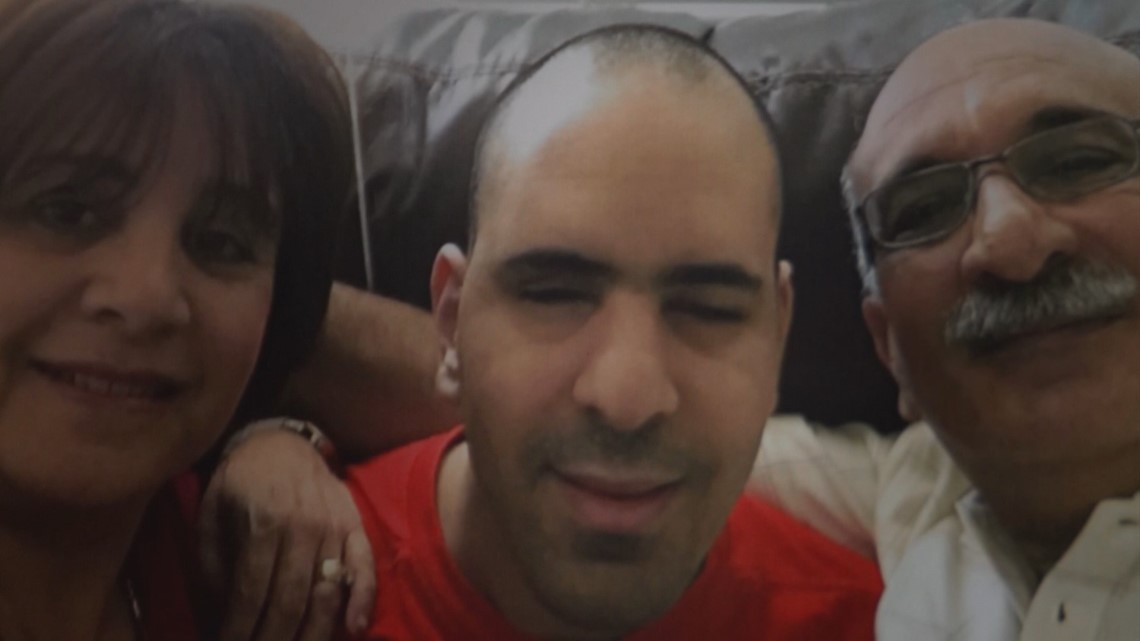

Mina Iskander also needed constant supervision. He’d been born severely premature. He was blind and intellectually disabled from birth. He lived with his parents Fawzy and Nevin Iskander until he was 22.

His parents, Coptic Christians who emigrated from Egypt decades ago, said they decided to let him live in a group home so he’d be with people like him.

He remained close to his parents and called them weekly. He was the only one of their three children to learn Arabic, they said.

The Iskanders have been searching for answers about what happened to their son since he died last December.

What they do know from police and state records is that on the evening of Nov. 27, 2018, Iskander and another disabled man made their way into the backyard of the Arlington adult care where they lived.

They left the yard through an opening in the fence where there had been once been a gate. They walked to a rocky embankment. Eight feet below is a creek.

Investigators got varying accounts about whether Iskander either fell or was pushed into the water.

No one at the house called 911 for an ambulance, according to police and state records.

Instead, one of the caregivers drove Iskander to Arlington Memorial Hospital. Records show he collapsed in the emergency room. He was then rushed to the trauma center at Harris Methodist Fort Worth.

His father, Fawzy Iskander, said a group home worker called and said his son had fallen and been taken to the hospital as a precaution. But in the middle of the night, he got another call, that his son was in critical condition at Harris Methodist.

“I got really shocked when I saw him,” his mother, Nevin Iskander, said.

Her son was covered with bruises. He had two fractured ribs and a fractured sternum. He was on a ventilator and unable to tell his parents or police what had happened to him. No one from the group home had stayed with him when he was first taken to the hospital -- a fact that seemed to puzzle the police who noted it in their investigation.

Iskander’s condition never improved. He died Dec. 10, 2018.

During their investigation, Arlington police would get conflicting stories of what happened to Iskander.

A caretaker told a nurse that Iskander had gotten into a fight. One worker initially told authorities that another resident hit Iskander in the face. Police described one of EduCare’s workers as “uncooperative.”

The disabled man who was with Iskander at the embankment told police that Iskander fell on a rock and hit his face. He then told police that he was “showing” him the creek when Iskander “tripped and fell in.” He also said Iskander “pushed him in the chest and that’s when Mina tripped and fell in.”

In a later interview at an Arlington police substation, where he was accompanied by his father, the disabled man told police he was “playing around with Mina near the water” and “my hand pushed him a little bit” causing him to fall in. He also said he was “holding Mina over the water so he could see it” when his hand slipped and Iskander fell.

Another disabled man who witnessed what happened initially told police Iskander and the other man were arguing when he “pushed Mina in the chest knocking off him of the edge into the creek.” He later told detectives that Iskander fell by accident.

A caretaker told police that she found the disabled man who was with Iskander at the creek crying in his room. She told police he said, “the devil told him to do (it). She believed he was talking about assaulting Mina,” the police records state.

“When everybody tells a different story, it makes me mad,” father Fawzy Iskander said. “Nobody wants to say the truth, say what happened.”

Natural causes

Despite his injuries, an autopsy by the Tarrant County Medical Examiner's office found Mina Iskander died of natural causes from a blood disorder called fungal vasculitis. The autopsy notes that he had a history with the disorder.

The medical examiner's office declined to talk to WFAA about the ruling, even off camera.

“I blame … the group home, the manager and the supervision,” mother Nevin Iskander told WFAA. “They are responsible.”

An EduCare administrator told state regulators that neither Mina Iskander nor the other disabled man required “staff with them always” or to be “visible to the staff,” according to state records obtained from the family’s attorney. Another staff member told regulators that Iskander – who was blind and mentally challenged -- was safe to go outside because he had a “high level of independence.”

State regulators did not agree. They found “the facility failed to ensure” Iskander was “monitored” and to “implement written policies and procedures that prohibit neglect,” state records say.

A month after Iskander’s death, the EduCare administrator told regulators he was not aware of the missing gate and said the company planned to put up a six-foot fence to limit accessibility to the creek.

When the gate and the fence had not been replaced a week later, staff members told regulators were “waiting on a check to fix the fence.” The state then declared an “immediate jeopardy” finding on Jan. 18, 2019, requiring the gate and fence be fixed. The repairs were complete Jan. 22 – almost two months after Iskander was injured.

The state is seeking to fine EduCare $26,800. The company is appealing. A hearing before a state administrative law judge is scheduled for late April.

“There’s a lot of evidence to show something wrong happened,” Fawzy Iskander said.

But there's no mention of what happened to his son is on the state’s long-term care provider database. The site lists routine state inspections from before Iskander was hurt for things like, “the facility failed to provide a well-maintained outdoor area.”

It lists no complaints and offers no clue that anyone was ever seriously injured there.

“Following the incidents at our Arlington and Pflugerville homes, we conducted thorough internal investigations and cooperated fully with local officials to determine exactly what happened and the proper steps moving forward,” EduCare spokeswoman Leigh White wrote in a statement to WFAA. “Unfortunately, due to HIPAA regulations, we are unable to share the findings of our investigations.

“Specifically, in Arlington, the staff followed the proper onsite emergency medical protocols for the safe and expedient transportation of those involved. Since the incident, we’ve implemented an addendum to the functional assessment given to all individuals in our care to determine if an individual requires additional supervision when outdoors.”

‘May God forgive us all’

Both the Iskander and Hunt families say they believe the state is failing to provide them and families like them the information they need to protect their mentally disabled children who cannot protect themselves.

“If you don’t know, you cannot make a proper choice on where your child is going to be placed,” Dorothy Fischer said.

On a crisp, sunny day last December 2018, Mina Iskander was remembered at a funeral at the St. Abanoub Coptic Orthodox church in Euless.

Amid chants and incense, a cousin recalled how Iskander gave the family the “gift of joy, love and laughter.”

“The world and our hearts will not be the same without you,” Michelle Hanvey said. “May God forgive us all. We could have done more.”

READ EDUCARE'S FULL STATEMENT HERE:

Send tips to WFAA Investigates at investigates@wfaa.com.

WFAA Investigates:

- Faked inspections, shoddy maintenance and lax oversight: Are Texas elevators safe?

- We had vaping products tested in a lab. Here's what we found.

- 'This is an outrage': Mother of autistic man angry Texas still slow to suspend bad caretakers

- 'They’re handing out these prescriptions like candy': Undercover DEA video shows pill mill in action