DALLAS — There are still days when all the energy Stephen Lummus has is to wake up and shower.

It’s been five months since he tested positive for COVID-19, but symptoms haven’t stopped.

“I am hanging in there,” Lummus said after a pause. “It's been challenging. I won't deny that it's changed our lives - all of our lives - considerably.”

He's dealing with everything from troubling heart arrhythmia to brain fog where he can’t remember words in the middle of a sentence and the constant fatigue that leaves him drained before his day begins.

“It wasn't anything I could work through, and that was the most frustrating,” he said.

There are a dozen medical terms or nicknames for people with symptoms that last a month or more after infections, but it’s often called long COVID, and those with it label themselves long haulers.

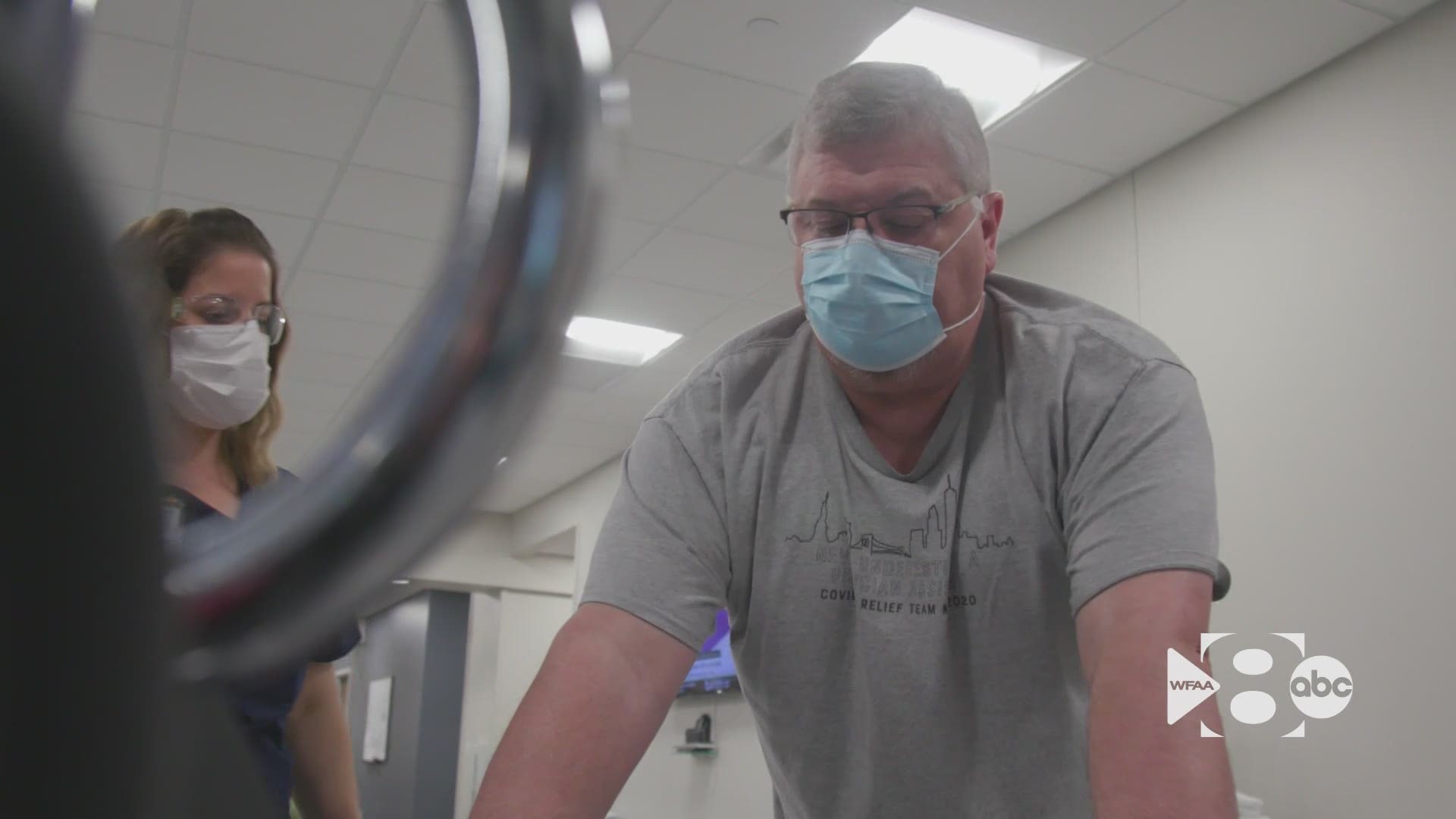

Dr. Juan Cabrera is part of UT Southwestern’s new post-COVID clinic, one of just a handful in the state designed for those with long COVID. It’s where Lummus has started rehab and demand is growing.

“I think it's probably more common than we realize,” Cabrera said.

Anecdotally, they’ve witnessed the same trends found in studies. Most people with long COVID were never hospitalized with the disease.

“The people that were really looking for the most help were the ones that were having the quote-unquote, milder cases of COVID,” he said.

What to know about long COVID

More than a year into the pandemic, much about long COVID remains unknown and long COVID is one of its greatest mysteries.

Health experts still don’t know for sure how common it is or why it happens. The World Health Organization estimates 10% of COVID cases still have symptoms 12 weeks after testing positive. Some estimates are up to 20% of cases have lingering symptoms for at least a month. Another study found 27% of patients had lingering symptoms for more than 60 days.

In the U.S., there are about 33 million reported cases. Texas has the next 3 million cases.

"There's a strong effort to do something for these individuals,” Cabrera said. “It's just a lot harder to find a program that is big enough and organized enough to actually market itself as a COVID program.”

Cabrera says fatigue and brain fog are the most common lingering issues along with loss of taste.

“It's not uncommon to hear people say, ‘I just wanted to get in the shower and halfway through the shower I just really wanted to curl up in a ball and take a nap because I had no more energy,” he said.

The CDC lists the symptoms that can also include headache, dizziness on standing, fast-beating or pounding heart, also known as heart palpitations, chest pain, difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, cough, joint or muscle pain, depression or anxiety and fever. The CDC defines them as people who experience symptoms four weeks after being first infected.

“It doesn't take much for me,” Lummus said. “I walk around the grocery store and I've got to sit down.”

From helping others to getting help

Lummus isn’t just a patient. He’s a provider, typically working as a physician assistant at urgent care in North Texas.

In April of last year, he traveled to New York City to help with the battle against COVID-19.

“It seemed like the right thing to do,” he said. “It was chaos, as organized as we could make it. Everybody was dying.”

He never tested positive, though, until December.

“I had a pretty good dose of denial going on at the time,” he said.

He was sick but never hospitalized until a month later when fading symptoms suddenly came back strong and put him in the emergency room.

“The shortness of breath got so bad and the fatigue, my staff of medical assistants were like - they were - they looked concerned,” Lummus said. “Healthcare providers, don't, we usually try to avoid seeking care for ourselves, but I went, and they put me in the hospital for a couple of days.”

He's been unable to work since, but symptoms and the bills haven’t stopped.

“We made the rent money this week this month. Yeah, this month just barely, and I don't know what's going to happen next month,” he said. “There's that part of me that says, yeah, this is kind of scary and that other part of me that says. Come on, Buck up man, you can do this.”

One of the many questions doctors still can’t answer is how long the lingering symptoms last.

“I'm very honest with my patients that I do not expect this to be forever,” Cabrera said. “But I do not know when it's going to end for each and every one of them.”

Lingering symptoms in children

It’s become clear children can be long haulers too.

There have been more than 3,000 cases of multi-inflammatory syndrome in children or MIS-C, where different body parts can become inflamed, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal organs.

Long COVID in children is believed to be significantly more common than MIS-C and surveys and studies have put the estimate around 10 percent.

“I don't think anyone knows the true long effects of COVID disease on children,” Suzanne Whitworth, the head of infectious diseases at Cook Children’s said.

Whitworth says the cases remain rare and they don’t have an exact count, but an increasing number of kids are showing up to different departments with different lingering symptoms that are keeping them out of school and sports.

“They can have GI symptoms of stomach upset, sometimes vomiting, headache, fatigue, sometimes difficulty concentrating,” she said. “For sure anybody that wants to go back to sports or other significant activities. If you've had COVID, you need to talk to your doctor and get clearance to play sports or be in athletics.”

She says parents should watch for signs.

“I'm too tired to go out and play with my friends. I'm taking naps when I didn't previously do that,” she said. “I think when the parents see and hear things that make them think things are not right, they need to call their doctor.”

Clinics in North Texas

UT Southwestern’s clinic uses a range of specialists, but one of the most valuable is its counselors.

“They told me I wasn't crazy,” Lummus said. “That was probably the first best thing that happened.”

“That is the piece that a lot of people are missing is yes, I'll put in the work to do therapy, but what about all of these other feelings and stressors that I have right now,” Cabrera said.

“I wish I could tell you that I didn't get discouraged and I stayed up all the time,” he said. “But it's - I know that it's caused some depression.”

The CDC still does not have guidance to treat long COVID but that information is expected soon. Because dealing with post-COVID symptoms is such a new practice, there are still few clinics.

John Peter Smith Hospital has a clinic for patients not recovering as expected. Texas Health Resources isn't currently planning a clinic and says it treats patients at primary and specialty care facilities. Parkland Hospital recently opened a clinic for people suffering from long COVID. Methodist Health System says it does not have a clinic for long haulers. Baylor Scott & White says it has rehabilitation clinics but none specifically named or dedicated to post-COVID symptoms. Baylor College of Medicine in Houston opened a clinic for long haulers in February and had seen or scheduled 260 patients by early May.

After 3 months on the waitlist, Lummus is a month into treatment at UT Southwestern.

“I've made quite a few improvements,” Lummus said. “I feel like I have more stamina. I feel like I'm able to do more things.”

There is no cure or clear treatment for long COVID, but a survey in the long hauler group Survivor Corps found around a third who get vaccinated have seen symptoms reduced and a UK survey found about 23% saw symptoms resolved.

Whitworth says it’s at least a way for parents and children to be protected.

“The main thing that they can do to prevent long COVID in their children who can't be vaccinated yet is to keep them from catching COVID disease in the 1st place,” she said. “We have to get vaccinated to make this all go away, we have to get the population vaccinated.”

“There's a lot of good people out there that are trying very hard to answer some very hard questions,” Cabrera said. “We may not have the answers yet, but every day we're getting a little bit closer to feel confident to come up with a plan for these patients.”

Stephen Lummus is on month five, and he isn’t alone. Symptoms haven't faded but neither has his motivation as a health care worker, a husband and a father.

“I think what keeps me going is that I want to return to that role of provider,” he said. “I have to.”