FORT WORTH, Texas — Cullen Davis doesn’t spend time thinking about the past.

It’s been roughly 40 years since he left his iconic Stonegate Mansion, and he never came back inside until WFAA invited him.

Soon, the property tied to Fort Worth history will be demolished.

The home has been a Mexican restaurant and, most recently, a wedding venue. Some of the original construction has been preserved, including its massive fireplace lounge and wood floors, but much has changed, and the large indoor pool was filled in.

“Looks like hell,” Davis said with a laugh standing in the former pool area. “This is the first time I've seen it at all since I moved out.”

Between Thanksgiving and mid-December, the iconic property of Fort Worth’s Hulen Street will be torn down.

4 years of construction, 5 bedrooms, 11 bathrooms, 13,000 square feet

“Anyone who’s been around Fort Worth is real familiar with the Stonegate Mansion, the Cullen Davis mansion,” said Kyle Poulson, one of the developers on the project. “To me, it was always an iconic piece of real estate in Fort Worth.”

Poulson says they’re working with neighbors, city council and Fort Worth Mayor Mattie Parker to finalize a plan on a 30-lot single-family development in the place of the home.

When it was built in 1971, the home was surrounded by a 250-acre field and, even today, the elevation allows for views for miles. It took four years to construct the property that included five bedrooms, 11 bathrooms and a 2,000-square-foot master bedroom — but planning for the 13,000 square foot mansion started much earlier.

“I spent nearly five years cutting pictures out of magazines off each room,” Davis said.

Davis gave the photos to architect Albert Komatsu.

“I said, 'Here's the way I want every room to look. You put it together efficiently,'" Davis said.

Adjusted for inflation, Stonegate Mansion cost more than $37 million to build, but Davis’ oil money at the time made him one of the wealthiest men in the country.

“I just wanted a place to have a party,” Davis said.

Its halls were filled with paintings and one living room held antiques. A living room to the right of the main entrance has had a wall torn down and bar area added, but Davis says it held jade, ivory and other antiques.

“I thought it would be more like it was when I lived here,” Davis said.

The mansion is best remembered, though, not for the paintings hung on its walls or its design, but instead, for the images and stories that once filled front pages and TV screens.

When asked if he had any memories in the home that stood out, though, Davis said nothing stood out.

"I really didn't have anything to speak of,” he said. “I can't think of a thing that I could speak about.”

Stonegate Mansion murders

'Can't change history'

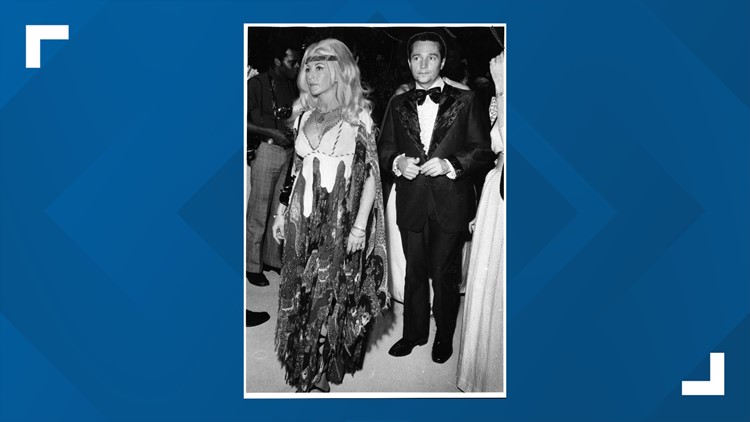

Six years after they were married and three years after construction finished, Cullen and his wife Priscilla Davis were separated, and a judge ruled Priscilla could live in the home. Then, on Aug. 2, 1976, a judge increased Cullen’s alimony payment to Priscilla to more than $23,000 a month in today’s dollars.

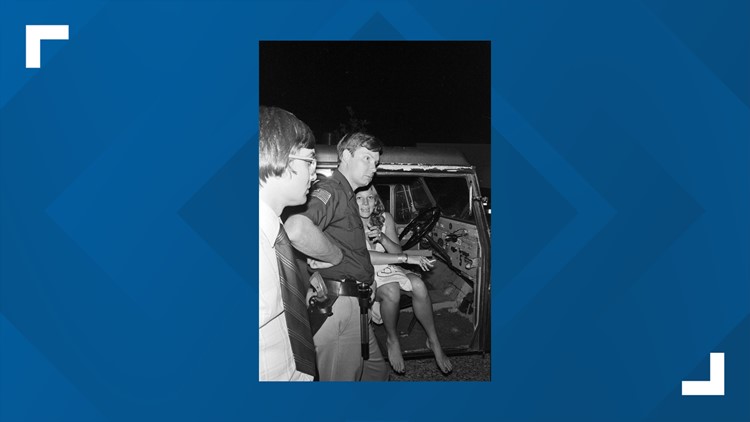

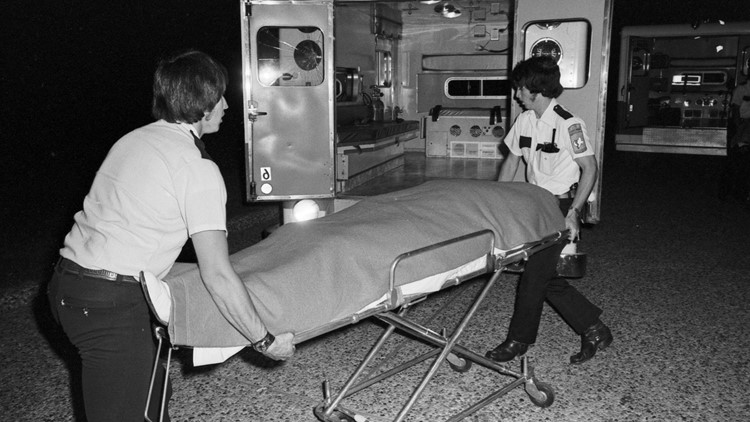

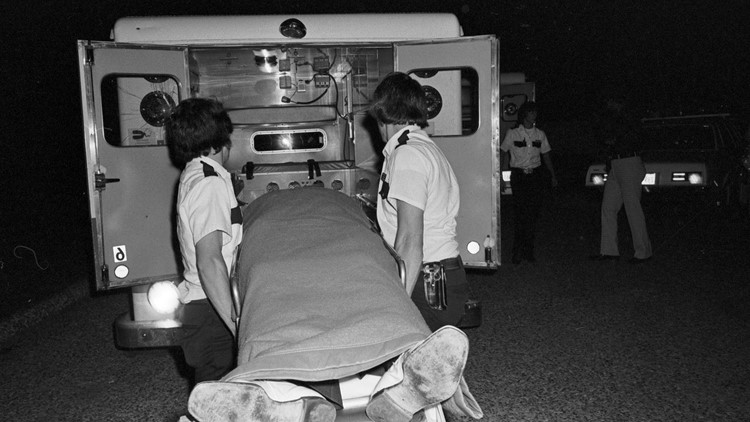

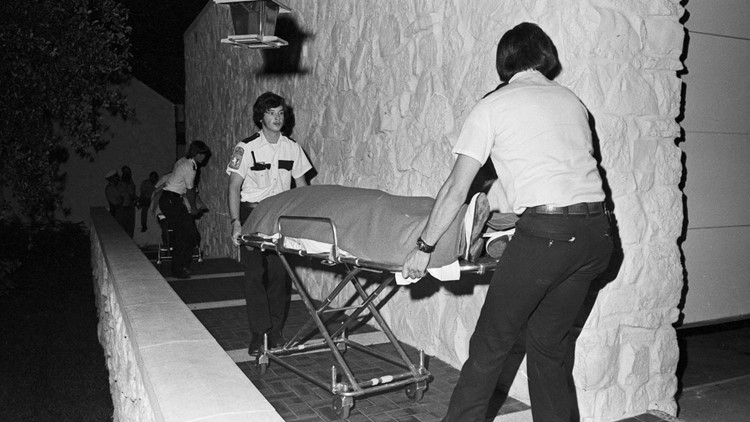

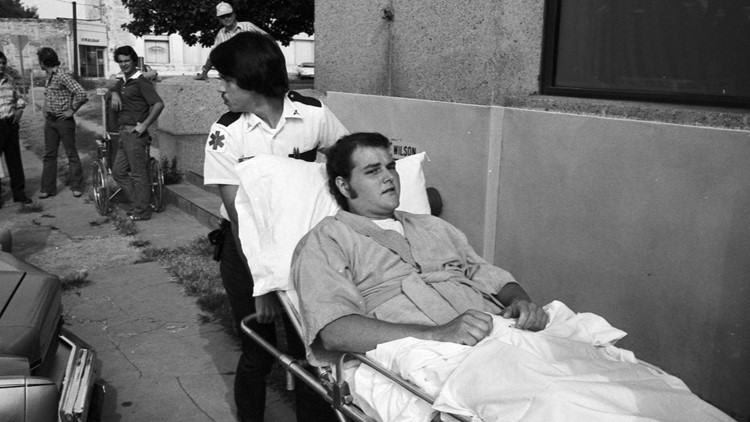

That night, an intruder, wearing black, broke into the home and shot and killed Priscilla’s 30-year-old boyfriend Stan Farr and her 12-year-old daughter Andrea Wilborn. Another friend, Gus Gravel, was shot and paralyzed. Priscilla was shot but survived.

RELATED: John McCaa profiles: T. Cullen Davis

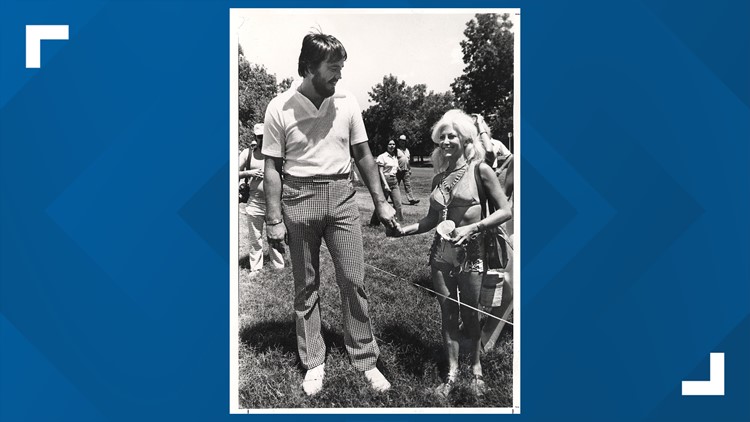

Eyewitnesses, including Priscilla, accused Cullen of the murders, but after an infamous trial that dominated news coverage, he was acquitted.

Two years later, Cullen Davis faced trial again for allegedly hiring a hitman to kill Priscilla and the judge in his divorce. He was acquitted again, though.

Davis says he ignores the many who still have doubts.

“I didn't care about that, either. They want to believe that, fine. What happened was unfortunate,” Davis said. “History is history. Can't change history.”

Some still want the home preserved as history. Others believe it should’ve been torn down decades ago.

“I had no reaction one way or the other,” Davis said. “I didn't care if they tore it down or kept it.”

“It’s a part of Fort Worth,” Poulson said. “I’m not saying it’s a good part of Fort Worth, but it’s history for Fort Worth.”

Davis claims his indifference started even before he declared bankruptcy claiming debts in the hundreds of millions of dollars and moved out.

“There was always something wrong with it. Some piece of equipment or something wrong that needed to be fixed every day I'd come home.”

The need for crews to fix problems is Davis’ explanation for a set of three connecting tunnels under the home that go more than a hundred yards out toward the edge of the property and are surrounded by 6-inch thick concrete. They eventually lead to a hatch at the surface.

“It was keeping stuff that made noise away from the house, like the pumps and the engines running them were noisy,” Davis said. “It was big enough for workers to go down there, and you can stand up in it.”

Davis, now 87, guesses about half the home has been changed since he moved out. Rooms have been added, and a large chandelier in the entryway has been replaced.

“It's kind of interesting that this is the first time I've been in the house since I moved out,” Davis said walking through the home.

Cullen Davis claims he doesn’t think about the past, but he’s a part of it.

Even demolished, the hill off Hulen Street will be connected to its past.