My bus passed a small convoy of twenty-seven ton 155mm self-propelled howitzers, their treads clanking on the pavement while driving over a bridge into the Demilitarized Zone. We emerged from our coach to the crackle of gunfire from a nearby army practice range. When we got closest to the DMZ itself, peering through a wintry haze at the North, there was opera blaring through loudspeakers over the valley below, part of a non-stop aural propaganda effort by North Korea.

The DMZ attracts more than four million tourists a year, drawn perhaps by the twinge of danger generated by two armies standing jaw- to-jaw. I was in Seoul, thirty-five miles away, working on other stories and wanted to get a feel for what South Koreans are thinking as the world wrings its collective hands over North Korea’s nuclear weapons.

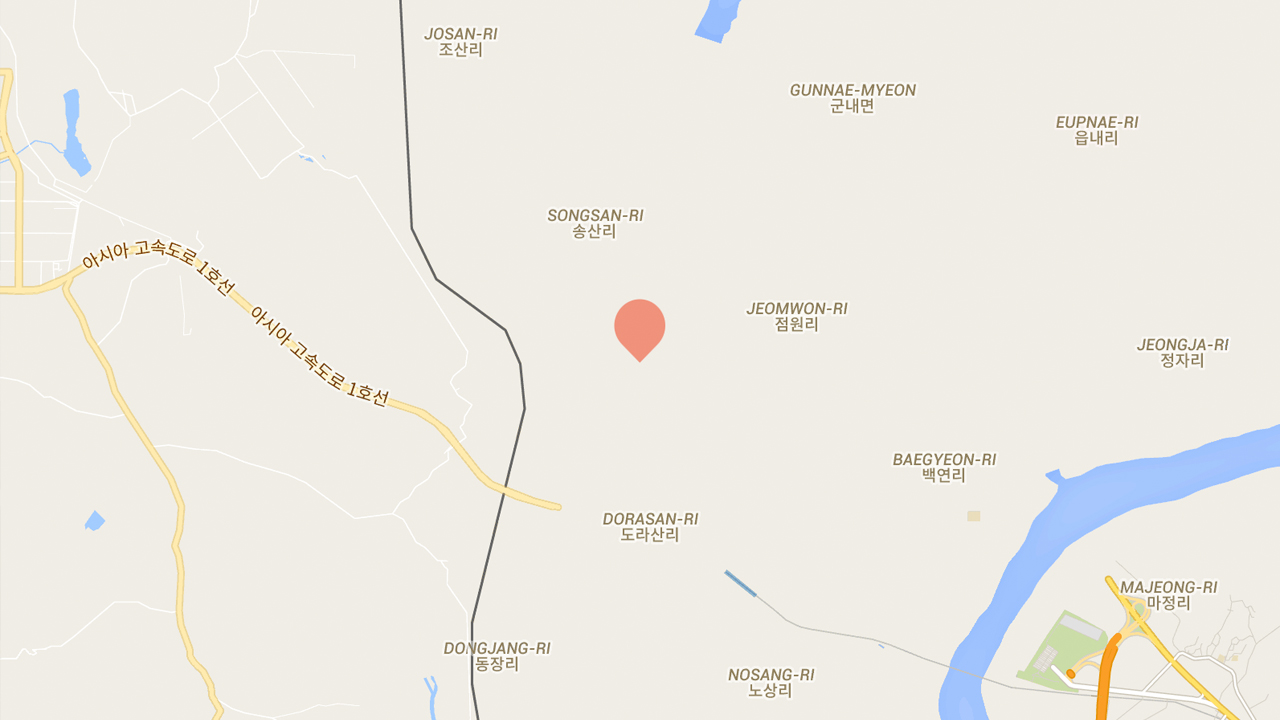

President Trump may talk about his “nuclear button,” and Kim Jong-Un his, but the DMZ is where the U.S. and North Korea have faced off every day since the Korean War ended in 1953. And it’s a likely focus of any conflict over nuclear weapons. Seoul, a city larger than Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio and Austin combined is seconds downrange, and the North Koreans already have their targets locked in.

The DMZ has always been hot. Historically, the two Koreas hold military exercises twice a year, in February and August. There are simulated launches of artillery missiles, real launches, feints, counterfeints, and consequences can result.

“A lot more happens there than people in the States realize,” LTC Ron Prowell, (Ret.) of Arlington told me. For two years, he was deputy chief of operations assigned to the United States Forces Korea in Seoul before retiring in 2016. One of his jobs was planning U.S. responses to a North Korean attack. “Incidents at the DMZ were common,” he said. “They don’t make the news back home.”

The DMZ is studded with reminders of how hot the cold war was, and how fiery the old hostilities between North and South could still be. Tourists can enter Tunnel Three, one of at least four tunnels the North Koreans dug deep under the DMZ that would have allowed them to clandestinely move troops into South Korea.

Nearly a mile long and more than six feet in diameter, descending twenty-five stories underground, Three had the capacity to move thirty thousand troops in an hour. The last tunnel, Four, was discovered in 1990. The South estimates that there are more, but the threat from the North has changed.

The South, which is to say Seoul, is now much more likely to be pulverized by artillery missiles and long-range cannons than it is to be invaded. It is one of the most densely populated metropolises in the world, bristling with high rise apartments.

My question in visiting Seoul and the DMZ, was this: Are South Koreans living in terror with this threat so near?

The resounding answer, after speaking to Koreans in Seoul and Dallas, and diplomats in Korea: No.

“Actually, we’re very used to this,” said Erica Kim, a 28-year-old Seoul resident. “We don’t really care about North Koreans and attacks.”

“That’s not going to happen,” said 36-year-old Anton Hur, a literary translator from Seoul, of attacks from the North. “Look at our stock market, it doesn’t fluctuate with threats, nobody thinks there will be military action.”

The Korean Stock Price Index, the KOSPI, went up twenty-one percent in 2017, and is up one point seven percent so far this year.

The fear, or lack thereof, may be somewhat generational. Erica Kim said her parents were concerned that Donald Trump’s visit to Korea in November might provoke action by the North. “They were born right after the war. So they still worry about the war,” she said. “But I don’t.”

The no-worry responses from others were quick and firm.

Anjin Jung, 35, of Seoul finished my question for me. “Am I worried about attack? No. I’m not worried.

“There will be no war,” a Korean trade representative in Dallas told me.

The exhibits at the DMZ send a starkly different, albeit mixed message.

At the DMZ Exhibition Hall, an eight-minute film urges tourists not to forget the 36,914 Americans killed during the Korean War. It is sharply anti-North. My tour guide told me the movie changes with the political winds occasionally during the year. Outside, a bronze sculpture depicts reunification of North and South, with ordinary citizens making a world whole again.

At the Dola Observatory, where one can actually see North Korea, the film was equally strident, with a “maybe someday we Koreas can actually get together” ending. Thousands of South Korean families have relatives in the North. But reunification would be costly for South’s booming economy, now the eleventh largest in the world.

This February’s military exercises have been postponed until after the Winter Olympics three weeks from now. The South has decided to let North Korean women's hockey players join their Olympic team, and march in the opening ceremonies under a new two-Korea flag designed for the occasion.

Comity is on the rise. But the weapons facing each other across the DMZ are still locked and loaded.